Protest Form Agains Unemployment Benefits Illinois

Harry Katz

During the early on 1930s, the largest protestation movement for unemployed people's welfare in U.S. history arose (Piven, 41). The motion sometimes succeeded in increasing local and state government spending on relief to unemployed people, increasing relief payments to individuals, and stopping individual evictions (Valocchi 1993, 459; Folsom, 270 and 276, Piven, 73). The unemployed motion besides trained activists who later became leaders in the labor movement of the 1930s, which is believed to have had a greater influence than the unemployed movement on the passage of the most meaning New Bargain laws (Lucia; Storch, 128).

The purpose of this inquiry projection was to learn nearly the unemployed move in Chicago, Illinois, in the early 1930s and the factors that contributed to the movement'southward successes and failures. The unemployed move in Chicago was one of the largest of any U.S. city (Bernstein, 428; Storch, 105). 1 feature that distinguished Chicago from the rest of the U.S. in the early 1930s was its especially loftier unemployment rate—40% of the workforce was unemployed in 1931 (Hallgren 1933, 119; Piven, 61). Chicago also had 1 of the worst fiscal crises of any large metropolis in 1932, and law repression of the unemployed movement in Chicago may have been unusually severe (Asher; Bernstein, 471; Fried, 133).

Unemployment During the Great Depression

During the Great Depression, the number of unemployed people in the U.South. rose from 429,000 in October 1929 to 12 million in March 1933 (Piven, 46, 66). In the early on 1930s, private charities and government agencies provided footling relief relative to the need for relief, and malnutrition and the rates of sure diseases increased (Piven, 41 & 48). Unemployment caused many people to become homeless, forced some parents to transport their children to friends, relatives, or organizations that were meliorate able to accept intendance of them, and harmed many people'south self-respect, since people often blamed themselves for losing their jobs (Ernest; Piven, 63; Valocchi 1993, 457).

Unemployed Councils

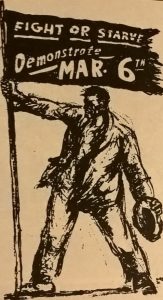

The Communist Party of the U.Southward.A. (CP) was the chief organization that mobilized the unemployed to take political action, and the political party did this by organizing local groups called Unemployed Councils (UCs) (Valocchi 1993, 455). There were UCs in most 340 cities and towns in the U.S. in 1932, and the UCs claimed 150,000 members in 1933. Membership figures tin can be unreliable, and many people who were not members of UCs participated in demonstrations organized by the UCs (Weyl, 118; Folsom, 275; Lorence, 289).

UCs prioritized coming together unemployed people'due south about urgent needs (Weyl, 118; American, 7-8; Allen, 685). Many UCs aimed to preclude evictions, dispute cases where relief agencies unfairly denied people relief, and meliorate atmospheric condition in bread lines, flophouses, and apartment buildings (Weyl, 118; Morrow). UCs also demanded increased relief expenditures from all levels of regime, unemployment insurance, government job programs, improved weather condition on government task programs, and an end to racial discrimination (Weyl, 118; Fried, 133; Valocchi 1990, 193).

In the early 1930s, UCs mainly used direct activeness tactics such equally physically resisting evictions, and UC organizers used pamphlets and speeches to persuade people to get politically agile (Piven, 68-69). UC organizers ofttimes spoke to unemployed people almost issues that the CP was concerned about that affected people in distant areas, such as the Scottsboro case and the Italian invasion of Ethiopia (Fisher, 46). The CP wanted UCs to educate people virtually these "translocal" problems, partly because the party hoped that all movements of workers would eventually unite into ane movement that served all workers' interests, and that the movements would unite under the political party's leadership (Fisher, 46; American, seven-8).

The CP was one of the only primarily white political organizations in the 1930s U.Southward. that advocated for equal rights for blacks and racial integration, and black and white activists created some personal bonds by working together in the UCs (Fisher, 44; Lucia). UC leaders devoted the nigh resource to organizing people in the poorest neighborhoods of their cities (Fisher, 45).

Food and Housing every bit Human being Rights Rather Than Commodities

In the early 1930s, the CP and unemployed movement leaders brought attention to the injustice of businessmen using food and housing to make a profit by selling these resource, while preventing people who could non afford the resource from using the resources to survive. For example, one statement by a Chicago unemployed arrangement observed that families did not accept adequate nutrient while stores and warehouses in Chicago were total of food (Hallgren 1933, 128). Similarly, at a demonstration organized by Chicago unemployed groups, one speaker said that hotels in the city had empty rooms while some people slept in Grant Park (NYT 11/1/32). In 1931, the editors of one conservative Chicago paper wrote that information technology fabricated sense that the Communists' messages were appealing to many unemployed people in the U.S., since the unemployed were suffering, and "everywhere about [the unemployed] is evidence of restricted enough in the greedy easily of a few" (Storch, 113). In the Low-era U.S., food sometimes rotted in the fields because low consumer spending fabricated it unprofitable for farmers to harvest the nutrient (Ross, 228).

Also, speaking at a Communist issue almost a group of 500 Arkansas farmers who asked for and and then took food from a store without paying for information technology, CP leader William Foster said,

"Comrades . . . why practise you workers admire the farmers in Arkansas for the bold stand up that they took? I will tell you why. I will tell you why the workers of this country admire that handful of farmers, because every worker in this country thinks the same thing in his heart, that is what the workers should practice, not stand up aside and calmly starve in the midst of plenty, but force them to give out of their stores" (Lasswell, 158).

Radical leaders asserted that the right to live was superior to the correct to profit, and the actions of many unemployed people in the early 1930s U.S. showed that they knew this. Planned, group annexation for food and other necessities was widespread in the U.S. by 1932 (Bernstein, 422; Piven, 49). Too, the unemployed motility's illegal physical resistance to evictions was an expression of the thought that tenants' survival was more important than landlords' profits (Folsom, 270).

Reject of the Unemployed Motility

The unemployed movement reached its greatest size in 1933 and and then began to decline (Valocchi 1990, 191, 201). Several changes may accept contributed to this reject. For example, 1933 New Deal laws that increased relief improved some unemployed people's conditions, and the promises of the new president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, made some people worry less (Valocchi 1990, 197; Lasswell, 182; Storch, 128). In Chicago, increased relief acquired the number of evictions to refuse from 63,152 in 1932 to 8,876 in 1934 (Storch, 128).

Also, UC organizers' rhetoric usually did not acknowledge the benign aspects of the 1933 New Deal programs, which may have made information technology less probable that some unemployed people who benefited from New Bargain programs would stay involved in the UCs (Valocchi 1990, 197; Valocchi 1993, 465). The New Deal also caused UCs to lose active members every bit some members gained employment with government job programs, and some UC leaders took jobs with New Deal agencies, including at least 2 leaders of Chicago's unemployed motion (Piven, 76, 79, and 85).

As well, in 1934, the CP shifted its focus from organizing the unemployed to organizing industrial workers, and moved some of its organizers out of UCs and into factories (Valocchi 1993, 458-459). The leaders of the unemployed move as well became more reluctant to criticize New Deal politicians, and began to discourage militant protests against government officials (Piven, 91; Valocchi 1993, 452).

There was significant turnover among unemployed activists, because many people left unemployed organizations in one case the organizations obtained more relief for their household, and unemployed people often constitute piece of work or moved to find work (Piven, 72; Lorence, 45). Every bit a result, fewer personal bonds developed betwixt activists, and this may have affected the longevity of unemployed organizations (Lorence, 45). Finally, many UCs began charging membership dues in early on 1934, which may have reduced the number of formal members (Valocchi 1990, 192; Piven, 72).

Chicago'due south Unemployed Movement

The two master unemployed organizations in early 1930s Chicago were the Chicago UCs, which claimed 22,000 members and 45 local branches in the early 1930s, and the Chicago Workers' Committee on Unemployment, which claimed 25,000 members in 1932 and 52 local branches in 1933 (Piven, 72; Hallgren 1933, 193).

The Chicago Unemployed Councils

Early in the Low, the Chicago UCs focused on increasing relief and stopping evictions, particularly in poorer neighborhoods (Fried, 133; Lasswell, 171). There were frequent eviction protests in Chicago, where crowds of people would attempt to physically terminate evictions (Piven, 54; Lasswell, 170). The protests often started when CP or UC leaders led people from Washington Park (a gathering place for demonstrations and political discussions in Chicago's South Side) to the site of an eviction (Storch, 99, 112). Eviction protests sometimes besides began when someone ran with news of an eviction to a local UC meeting hall (Lasswell, 170).

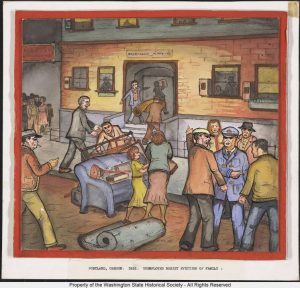

Unemployed people, who often socialized and relaxed in UC meeting halls, would so march towards the site of the eviction, and people would meet the marchers and join them on the style (Lasswell, 170). These crowds would oft move the evicted person'southward furniture back inside and so gradually disperse (Lasswell, 170). Eviction protests sometimes had thousands of participants (Storch, 112). Eviction protests were oftentimes successful, because large crowds sometimes deterred law from interfering and landlords sometimes gave upwards on trying to adios people (Weyl, 118; Folsom, 270). Anti-eviction organizing by the UCs was concentrated on Chicago's South Side (Storch, 112).

Chicago UCs also held demonstrations in front of relief offices (such as the demonstration in the picture to the correct) where crowds would need relief for someone who had been denied relief or was not receiving relief in a timely manner (Lasswell, 171). People used coin from relief offices for rent, nutrient, clothing, fuel, or utilities (Storch, 116). Chicago UC protesters sometimes sat down in relief offices until their demands were met or police arrested them (Lasswell, 180). Relief office protests were often planned when UC activists who belonged to UC sub-groups called block committees learned of the desperate situation of someone on their block, and the activists knocked on the doors of everyone on the block (employed and unemployed) to invite them to a coming together almost supporting their desperate neighbor (Storch, 105). At the meeting, the neighbors would decide what to do to help the person (Storch, 105). Relief office protests were the main focus of UC activity outside of the South Side (Storch, 116). Victories from these protests gave people a sense of their collective strength, led more people to participate in UC actions, and also led more people to tell the UCs about their private problems related to relief or evictions (Lasswell, 171).

The Chicago UCs also turned on the gas, electricity, and water of some unemployed people who could non pay their bills and left signs saying "Restored past the Unemployed Councils" to build their reputations, and organized for better conditions in flophouses (Storch, 103, 109, & 112-113).

Chicago UCs were largest in Chicago's South Side neighborhoods, and the UCs' members were mainly adult, male, unemployed people (Storch, 125-126). Although Chicago UC leaders encouraged women to join UCs and told male UC members to welcome women, women in many UCs tended to be given less powerful positions than men. Then female activists formed most 20 women's committees in Chicago in 1933 (Storch, 125-126). The women's committees often promoted the UCs and participated in UC actions, while as well fighting for several demands that the UCs did non usually fight for, such as relief in the course of pots and pans (Storch, 125-126).

Chicago UC members elected block committees, which each represented ane or two city blocks (Folsom, 265). Block committees sent delegates to neighborhood UCs (Folsom, 265). Neighborhood UCs sent delegates to the Chicago UC, with the number of delegates depending on the size of the neighborhood UC (Folsom, 265).

Chicago police frequently concluded UC demonstrations using violence or arrests (Lasswell, 169). The police force also sometimes arrested UC organizers for distributing leaflets and broke up indoor UC meetings (Lasswell, 168).

Chicago UCs organized large interracial protests, sometimes on a scale that the city had not seen before (Storch, 114-115). In Chicago'due south UCs, which were racially integrated, black and white activists worked together, including some whites who had never spoken to blacks before, and vice versa (Storch, 115). 1 black activist reported that they felt respected and that they could speak freely at UC meetings, even though they unremarkably had non felt this manner earlier in the presence of whites (Storch, 115).

Chicago UCs taught skills related to activism to people who had not previously been politically involved, such as public speaking and challenging constabulary officers and relief officials (Storch, 129). Also, many activists who gained skills in Chicago's UCs became leaders of the Chicago CP or Chicago's labor unions later in the 1930s, although these people did not necessarily gain their first feel with activism in the UCs (Storch, 103 & 128).

The Chicago Workers' Committee on Unemployment

The Chicago Workers' Committee on Unemployment (CWCU) was created in mid-1931 by members of the League for Industrial Democracy (Hallgren 1933, 193). Like the Chicago UCs, the CWCU held relief office demonstrations, and organized larger relief part demonstrations if their demands were not met (Weyl, 120). The CWCU besides had grievance committees in most of Chicago's relief offices that inspected relief officials' work (Weyl, 120). The CWCU also organized a Speakers' Bureau of volunteers who came to meetings of its local branches to teach people about economic bug, unlike proposed relief policies, and other aspects of economics (Asher, 168). Most of the CWCU's members were poor relief recipients (Asher, 168).

The CWCU engaged in a successful campaign to prevent relief offices from closing in Cook County, where Chicago is located, although I do not know whether the CWCU's efforts played the decisive office in this victory. In May 1932, the Illinois Emergency Relief Committee (IERC) announced that it was closing its relief offices due to relief funds beingness exhausted (Asher, 169). The CWCU sent delegations to city newspapers to demand that the newspapers report on the result (which some newspapers agreed to practice), asked for and received time on local radio stations to land its position, and lobbied the urban center'southward wealthiest bankers to lend several million dollars to the county government to proceed the relief offices open (Asher, 169). Several days after the IERC's announcement, and the day before the relief offices were scheduled to close, local bankers loaned the canton government more coin than the CWCU had asked for—enough to keep the relief offices open for two more months (Asher, 169).

Although both the CWCU and the Chicago UCs called for a club controlled by ordinary workers, the CWCU differed from the UCs in that its leaders did not believe a revolution was probable in the most future (Lasswell, 276). CWCU leaders besides did not refer to struggles in other countries every bit oft equally UC leaders, who held many demonstrations virtually issues in other countries (Lasswell, 276). The CWCU also tended to use less confrontational and confusing tactics than the UCs (Lasswell, 276).

One factor in the decline of Chicago'southward unemployed motility was that in 1933, Chicago relief officials began a policy of refusing to respond to unemployed groups' protests, and Chicago police repression of protests in forepart of relief offices increased (Storch, 121; Lasswell, 180-182). Concessions granted past relief officials subsequently relief part protests had helped unemployed groups to concenter members by showing people that protests could pb to improvements in their lives, so the increased repression of relief office protests made it more difficult for Chicago unemployed groups to attract members (Storch, 121; Lasswell, 181).

Chicago Demonstrations and the Reversal of Regime Decisions

The Chicago unemployed motion's demonstrations against relief cuts (and in one case the movement'southward annunciation of a demonstration) in the early on 1930s probably caused some relief cuts to exist withdrawn. Information technology is usually difficult to evidence that a protestation tactic led to a social alter (or to demonstrate that causal connections existed between different historical events in general), because for most social changes, there are a large number of factors that could take plausibly contributed to the changes. Also, information technology is ordinarily hard to mensurate the relative importance of diverse factors in producing a given social modify.

However, instances where governments made decisions and then reversed those decisions a short time after make it simpler to place the reasons for policy changes, because the brusque time periods limit the number of events that could have acquired the governments to opposite their decisions. If an event happened before the original determination, and so information technology is unlikely that the effect caused the government to reverse its determination, considering the event did non prevent the government from making its original decision. These kinds of situations might exist some of the closest things to controlled experiments in the historical record.

In the early 1930s, there were several instances when Illinois authorities cut relief, then rapidly reversed their decisions after big demonstrations by unemployed groups. These kinds of prompt reactions past local governments to unemployed protests against relief cuts were evidently common in the early 1930s U.Due south. (Hallgren 1933, 192). In each of the examples beneath, the only event I know of that happened in the fourth dimension between the decision to cut relief and the decision to restore relief, and that could have caused the decision to restore relief, was a protest by unemployed groups.

On October 1, 1932, Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak announced that the urban center would cut relief payments by half due to relief funds beingness exhausted (Fried, 134; Hallgren 1933, 132). The UC and the CWCU jointly organized a peaceful march of 10,000-50,000 people on October 31 that went by City Hall (Piven, 59-60; Storch, 122-123; Hallgren 1933, 132; NYT 11/1/32). (Run across the two pictures of this demonstration beneath.) The demands of the march included a withdrawal of the relief cutting, an increase in relief, an stop to evictions, and an end to workplace racial discrimination (Fried, 134; NYT 11/i/32). After the sit-in was announced, but before it took place, the secretarial assistant of the Illinois Emergency Commission on Unemployment (IECU) successfully persuaded the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to loan the IECU $6,300,000 to allow the continuation of relief, and Mayor Cermak announced that the cut would exist withdrawn soon afterwards the demonstration (Hallgren 1933, 194).

Besides, in 1934, the Chicago City Council voted to cut food aid by 10%, leading to a large demonstration past primarily unemployed people, after which the city quango restored the food aid (Piven, 67). Likewise, in 1935, Illinois stopped receiving federal relief money because the state government was not contributing plenty relief, causing some relief offices to close (Piven, 67). Primarily unemployed people demonstrated in Chicago and the country capital of Springfield until the land legislature dedicated enough land funds to relief to restore federal relief (Piven, 67).

While these demonstrations probably caused relief cuts to be withdrawn, it is unclear how the demonstrations led to these victories. The demonstrations may have shown politicians the level of anger that the unemployed felt about specific grievances, and made the politicians fright the possibility that the unemployed would engage in violent protests if the grievances were not addressed. Some unemployed demonstrations aimed to create this kind of fear in politicians (Weyl, 118).

As well, the unemployed movement'south demonstrations often increased public and media attention to the plight of the unemployed (Weyl, 117; Bernstein, 427), partly because the demonstrations showed that there were many unemployed people who were suffering plenty that they were willing to march. This increased public consciousness of unemployment may have made elected officials more than eager to seem like they were responding to the social problem in order to protect their reelection chances.

Chicago Unemployed Councils' Organizing in the Black Customs

The UCs were more successful in organizing members of Chicago'due south black community than other radical organizations in Chicago (Storch, 113). One writer estimates that in 1934, 21% of Chicago UC leaders and 25% of Chicago UC activists were blackness, and the CP and the UCs developed positive reputations in parts of Chicago'due south black community (Storch, 111, 113, 115). Chicago's population was 6.9% black in 1931 (Storch, 111). One reason why Chicago's UCs had many black members was that the largest UCs were on the South Side, where unemployment was the highest (Storch, 112, 125), and the Due south Side was disproportionately blackness. Also, two of the main activities of Chicago's UCs were helping potential relief recipients and stopping evictions, and Chicago'southward relief recipients and victims of eviction were disproportionately black (Storch, 112).

At that place are several other factors that may have contributed to Chicago UCs' successes in organizing black people. Chicago UC leaders spoke at existing institutions and existing gathering places for activists in the black community (Storch, 111). For example, UC activists spoke at predominantly blackness churches and met with the ministers of the churches (Storch, 112). UC activists also held demonstrations and spoke regularly at Washington Park (one of the major gathering places for demonstrations and political debates in Chicago'south black customs) sometimes to thousands of listeners of all generations (Storch, 99, 111). The UCs had many black leaders, and members of the public often saw black UC organizers leading demonstrations (Storch, 112). Also, in their speeches, UC leaders emphasized their opposition to bigotry confronting black people in Chicago and other areas of the U.S. (Storch, 112).

Relief Actions and Chicago Officials' Fear of Violent Protests

Fright of violent protests by the unemployed probable caused Chicago metropolis officials to grant more relief and a temporary stop to evictions and rent in 1931, and probably increased Mayor Cermak's willingness to lobby the federal government to transport relief money to Chicago in 1932. Although Chicago officials' concern near the possibility of violent protests might aid to explain the officials' decisions regarding unemployment relief, this does not mean that the officials' concern about potential violence was created by the Chicago unemployed move's strategies, or that increasing business concern about potential violence is the well-nigh effective or ethical strategy of achieving policy changes in whatsoever context.

Aftermath of Shootings by Constabulary at a 1931 Eviction Protest

On August 3, 1931, in Chicago'due south South Side area, UC leaders encouraged a crowd of people in Washington Park to walk to the site of an eviction a few blocks abroad and move the evicted person's piece of furniture back inside (Lasswell, 196-197; Storch, 99). During the eviction protest that followed, Chicago constabulary shot and killed two to iv blackness protesters, and three police officers were injured (Storch, 99-100; Folsom, 268; Grossman).

According to one Chicago UC organizer, the murders created profound anger, including in people who had non previously been politically active (Fried, 134). Beginning hours later the shootings, Chicago Communists distributed fifty,000 pamphlets calling for the police officers who had committed the shootings to receive the death penalty (Fisher, 44; Lasswell, 198). Political meetings in Washington Park drew five,000-10,000 people every evening for several days after the shootings, and about 40,000 black people and xx,000 white people attended the funeral of the victims (Storch, 100; Hallgren 1933, 179).

City newspapers focused on the shootings, and Chicago residents exterior of the S Side, became fearful that there would be violent protests in the South Side, i of the well-nigh economically and racially oppressed areas of the city (Lasswell, 197-198). After the shootings, city officials sent ane,500 policemen into South Side neighborhoods, policemen dispersed any gatherings on the Due south Side, and several National Guard units prepared for action (Lasswell, 198; Hallgren 1933, 179), showing that Chicago elites were concerned near potential violent protests.

Chicago elites may take been afraid that South Side residents would commit violence in response to the shootings, particularly in calorie-free of the outpouring of anger expressed by the large, nonviolent gatherings subsequently the shootings. The elites may also take been afraid that the unusually violent conflict betwixt protesters and police was a sign that S Side residents were condign more frustrated with their social conditions, and were therefore condign more probable to appoint in violent protests.

Soon later the shootings, Cermak ordered a temporary moratorium on evictions in Chicago and a temporary moratorium on rent, and the city authorities expanded its relief program (Piven, 55; Fisher, 44; Storch, 115). The argument that some writers have made that these policy changes resulted from city elites' fearfulness of trigger-happy protests on the South Side seems likely to be truthful considering that city elites' deportment testify that the shootings increased the elites' concern that people would engage in trigger-happy protests, and that the policy changes happened shortly after the shootings (Lasswell, 201; Fisher, 44). If this argument is correct, then the specific policy changes that city elites chose to avert tearing protests show that the elites were afraid of violent protests by the poor and the unemployed.

Mayor Cermak'due south Requests for Federal Relief in 1932

In June 1932, Chicago was experiencing a severe financial crunch. Both the city and county governments were bankrupt and in debt (Hallgren 1932, 535). Salaries were months overdue to metropolis workers. Local relief funds were exhausted. State relief funds were expected to run out in several weeks, and the state legislature refused to allocate more funds for relief (Bernstein, 467). Meanwhile, there were about 750,000 unemployed people in Cook County, only about 100,000 of whom were receiving relief (Bernstein, 467; Hallgren 1932, 534-535).

On June 21, 1932, Cermak told a congressional commission that if the federal government did not ship $150 million for relief to Chicago immediately, they would have to send troops later, implying that without relief, the unemployed would engage in a tearing rebellion (Bernstein, 467; Piven, 61). In July, Congress passed the Emergency Relief and Structure Act, which allocated $300 million in loans to us for relief (Bernstein, 469), to be administered past the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC). Because of the fiscal crisis in Chicago, Illinois was the first land to receive a loan under this law (Bernstein, 471). In August, the RFC lent another $6 million to Illinois, saying that information technology would non lend to Illinois again unless the state legislature contributed more than money to relief (Bernstein, 471).

In September, Cermak asked the RFC for $9 1000000, saying that Chicago had run out of relief coin, and without a new loan, Chicago's relief offices would shut (Bernstein, 471). Cermak told the RFC directors, "I want this commission to know and the Governor to know that the stations should non be closed till afterward the Militia has been called" (Bernstein, 471). Despite the fact that the Illinois legislature had not contributed to relief since the RFC'southward asking for the legislature to do and then, the RFC lent Illinois some other $5 one thousand thousand in September (Bernstein, 471).

It is possible that Cermak was not genuinely concerned that the closing of Chicago's relief offices would atomic number 82 to a violent rebellion by the unemployed, and that he only raised this possibility in his lobbying because he believed that information technology would frighten federal officials. Also, there is niggling prove that the decisions of Congress or the RFC were influenced past Cermak's warnings about the possibility of violence by the unemployed. All the same, the near plausible explanation of these events seems to be that Cermak's fear of violent rebellions by the unemployed (which also expressed itself in Cermak'southward response to the police shootings discussed above) increased Cermak's desire to anteroom the federal regime for relief funds.

Harmful Furnishings of Strict Communist Party Control on Chicago'due south Unemployed Councils

Although the Chicago UCs had some autonomy from the national and Chicago CPs, the CP largely controlled the Chicago UCs' political positions and strategies in the early on 1930s. The national system of UCs did not adopt a constitution until 1934, considering the national arrangement wanted to allow for local variation across its fellow member organizations. Chicago CP officials wrote of the importance of local variation amidst the UCs due to variation among Chicago's neighborhoods. (Folsom, 267; Storch, 107).

Also, Chicago UCs varied in their structures and goals. Local UCs sometimes voted down CP decisions, and UC leaders sometimes worked with organizations that the CP did not approve of, over the CP'southward objections (Storch, 102, 107 & 124). However, the CP largely controlled the political positions and strategies of the UCs, partly through the party'due south power to miscarry leaders of local UCs (Storch, 124; Fisher, 42-43). For instance, the CP dismissed ane Chicago UC leader who publically questioned the CP's decisions (Storch, 124).

The degree of control that the CP exercised over UCs in the early on 1930s U.S. probable decreased the UCs' effectiveness past decreasing experimentation with new tactics, decreasing democratic determination-making, and encouraging the UCs to denounce other left-wing organizations. The CP'southward control over UCs fabricated information technology difficult for the UCs to experiment with new tactics that may have increased their effectiveness (Valocchi 1993, 461). 1 of these new tactics was increased cooperation with other organizations, which Chicago UC organizers sometimes felt was beneficial, but which the CP often discouraged, because many of the other organizations were non as radical as the CP (Storch, three, 123-124).

The CP'due south efforts to control the UCs (which included discouraging the UCs from putting the CP's decisions to votes) likewise decreased democratic conclusion-making in the UCs (Storch, 124; Valocchi 1993, 462-463). This may have decreased the UCs' effectiveness past causing some ideas from people who knew more than about local weather than the national party to be excluded, and creating resentment amid some members of the UCs.

Also, the UCs' aggressive condemnation of other left-wing organizations, which the CP encouraged, likely alienated some unemployed people who supported the other organizations (Storch, 123 and 129). For example, Chicago UC leaders gave speeches condemning the leaders of the CWCU (Storch, 123), which was perhaps the largest unemployed organization in the city, and this likely alienated some of the CWCU's supporters from the Chicago UCs.

One author also argues that certain UCs that were more autonomous from the CP than UCs in cities like Chicago, had more than members and less turnover than most other UCs, and certain other relatively autonomous UCs managed to maintain their levels of activity and public participation after the 1933 New Bargain reforms, when many UCs began to turn down (Valocchi 1993, 461-462; Valocchi 1990, 198). However, more research is needed on why certain more autonomous UCs seem to take had more stable public participation than many other UCs.

The Presence of Skilled Political Organizers

Although the widespread economic destruction of the Depression fabricated the growth of a big unemployed movement more probable, skilled political organizers from the CP and other organizations facilitated the growth of the motion in the early 1930s U.S. past helping to move many economically devastated people to action (Valocchi 1990, 193-194; Valocchi 1993, 463; Goldberg). The CP sent organizers to cities to help to build local UCs, and paid the organizers stipends (Fisher, 38-39 and 42-43). UC organizers spoke to unemployed people at breadlines, relief offices, flophouses, factory gates, and on street corners (Fisher, 40-41). In 1930, one Communist official claimed that UC organizers had distributed millions of leaflets to organize the unemployed, and had helped to organize several demonstrations in most large U.S. cities (Piven, 75).

One writer argues that in the contemporary U.S., labor unions are well positioned to help progressive social movements to grow by providing additional skilled organizers and funding to those movements (Goldberg). The writer explains that U.S. labor unions own $34 billion in avails and have millions of members who are disproportionately progressive (Goldberg).

The Characteristics of Many Unemployed Council Organizers and Activists

The courage and persistence of many UC leaders and activists in early 1930s Chicago contributed to the successes of their organizations. For instance, some Chicago UC leaders were arrested scores of times, oftentimes without having committed crimes, and Chicago UC leaders sometimes reported existence beaten by law officers while they were in constabulary custody (Hallgren 1932, 535; Hallgren 1933, 129-130; Fried, 133; Lasswell, 177, 179; Storch, 118). However, later on being released from police force custody, the organizers returned to piece of work scores of times.

UC activists also continued to protestation despite facing trigger-happy police repression. Activism continued despite the fact that Chicago police officers sometimes used fire hoses to break upward eviction protests, and sometimes beat people at relief office protests, including children (Storch, 118). Participants in eviction protests sometimes refused to movement when the police beat them or pointed guns at them (Cayton, 155-156). Co-ordinate to a reporter, on one occasion, when a police officeholder pointed his gun at a crowd of black Communist protesters who were going to terminate an eviction, the crowd stood even so (Cayton, 156). One immature man stepped out of the crowd and told the officeholder:

"You tin't shoot all of us and I might as well dice now equally any time. All we want is to come across that these people, our people, get back into their homes. We accept no money, no jobs, and sometimes no food. Nosotros've got to live some place. We are only interim the way you lot or anyone else would act" (Cayton, 156).

The activist'south words prove how much he cared well-nigh the survival of other people in his community. For some organizers and activists, the first-hand experience with vast homo misery that they gained from working with the poorest members of society in the UCs, combined with their business for others' welfare, likely led them to take more risks and work more than persistently. One writer believes that the commitment of U.S. UC organizers (who were commonly CP members) partly derived from their sense of solidarity with other activists, their Marxist-Leninist education, and the moral authority of the CP (Valocchi 1993, 456; Fisher, 43). One potential question for farther research might be why many UC organizers and activists showed such a strong commitment to their political piece of work.

News Media Coverage of Chicago's Unemployed Movement

Well-nigh news articles that I read in The New York Times almost unemployed protests in Chicago during the early on 1930s focus on what happened during the protests themselves, especially any violent clashes that occurred between protesters and police officers, and comprise very little discussion of the political issues that the protests were near (NYT 3/vii/xxx, NYT xi/25/xxx, NYT 11/26/32, NYT three/v/33). However, some of the Times articles present the Chicago unemployed groups' perspectives past including long quotes from the groups' leaflets (NYT 2/22/30) or discussing the speeches that were given at the groups' demonstrations (NYT 11/1/32).

The articles that I read in The New Republic and The Nation about the unemployed movement in the early 1930s contain national overviews of the motility or more than detailed discussions of the movement'south activities in individual cities (Morrow, Weyl, Asher). These articles provide more data on unemployment and the unemployed movement than the Times manufactures that I read. Even so, this may partly be because the Times articles are news articles that limit themselves to discussing private events such equally protests, whereas the other manufactures are non news articles.

Also, different the Times articles, the manufactures in The New Commonwealth and TheNation articles accept positions on the move's demands. For example, one 1932 New Republic article near the unemployed motility in Chicago states, "[the unemployed] have no intention of watching an incompetent administration plunge them over the cliffs without themselves putting a hand to the reins. They refuse to starve" (Asher, 168).

Conclusion

The fact that some relief cuts in the early on 1930s were promptly withdrawn subsequently demonstrations past Chicago's unemployed movement indicates that the move's demonstrations probably caused the government to withdraw some relief cuts. Also, the Chicago UCs were relatively successful in organizing blackness residents of the city, perhaps partly because UC leaders spoke at existing institutions and gathering places in the black customs, UCs had many black leaders who were visible to the public, and UC leaders were outspoken opponents of racial discrimination. The Chicago city government's fear of violent protests by the unemployed likely caused the government to grant more than relief and event temporary stops to evictions and the charging of rent, and probably increased the mayor's willingness to lobby the federal government for relief.

Also, the CP's control of the UCs, including the Chicago UCs, likely decreased the UCs' effectiveness past decreasing tactical experimentation and democratic controlling and encouraging the UCs to condemn other left-wing organizations. Additionally, skilled political organizers increased the membership of the U.S. unemployed movement, and the backbone and persistence of many UC leaders and activists contributed to the successes of their organizations. In the U.S., Communists and local unemployed motility leaders brought attention to the injustice of withholding food and housing from poor people in order to sell these resources equally commodities for a profit, and promoted the idea that people had a right to these resource.

Instances where governments make decisions so quickly contrary their decisions after activities by social movements tin provide especially disarming evidence of social movements influencing policy. This is because there are a express number of events in the short time periods between the decisions and their reversals that could have caused the governments to reverse their decisions.

Some questions that might exist interesting to inquiry farther are why many UC organizers and activists showed such a strong commitment to their political piece of work, why sure UCs that were more democratic from the CP seem to take had more stable public participation than many other UCs, what lessons about interracial organizing tin can be drawn from the unemployed motion, and whether labor unions in the contemporary U.South. tin can devote more than of their resources to helping progressive social movements to grow.

Sources

Allen, A. (1932, August). Unemployed Work—Our Weak Signal. The Communist, 681-685.

American Civil Liberties Wedlock. (1935). What Rights for the Unemployed? : A Summary of the attacks on the rights of the unemployed to organize, demonstrate and petition. New York City.

Asher, R. (1932, September 28). The Jobless Help Themselves: A Lesson from Chicago. The New Republic, 168-169.

Writer unknown. (1930, February 22) Chicago Crimson March Routed at City Hall. Oversupply of ane,200 Jobless, Led past Communists, Are Charged by Mounted Police. Heads Battered, 12 Held. Mayor Thompson Guarded by Detectives—Demonstration Incited at Radical Meeting. The New York Times.

Writer unknown. (1930, March 7). Many Injure in Riots in Nation's Cities. Mounted Police Charge Crowds in Detroit and Cleveland During Red Rallies. 25 Injured in Pittsburgh. Order Prevails in Philadelphia and Chicago—Mayor Receives San Francisco Marchers. The New York Times.

Author unknown. (1930, November 25). fifty Jobless Invade Chicago City Hall. Group is Routed Earlier it Can Enter Quango Sleeping accommodation—Communists Are Blamed. The New York Times.

Author unknown. (1932, November i). ten,000 Chicagoans Join 'Hunger march.' Chanting "We Want Breadstuff," Men, Women and Children Move in Rain Through Streets. Concur Peaceful Meeting. Exhorted by Reds While Demands for Cash for Unemployed are Presented to Mayor Cermak. The New York Times.

Author Unknown. (1932, Nov 26). Capital Groups Warn the 'Hunger Marchers.' They Will Not Get Free Nutrient and Lodging—Group of 350 Starts From Chicago. The New York Times.

Author unknown. (1933, March 5). Idle March in Chicago. 12,000 Protest at Relief Cut – Brief Clash Occurs equally Soviet Flag Tramped. The New York Times.

Bernstein, I. (1960). The Lean Years: A History of the American Worker 1920-1933. Cambridge: The Riverside Printing.

Cayton, H. (1931, September 9). The Black Bugs. The Nation.

Cox, D. (2012, January thirteen). The unemployed workers' movement of the 1930s. Workers World.

Ernest, Yard. (1933, October ane). Transients to Go Relief in Illinois. Eight Centres for Homeless and Jobless Planned by Federal Agency. Rehabilitation is Aim. Many of the Wanderers are Less Than 21 Years Old—Come From Various States. The New York Times.

Fisher, R. (1994). Allow the People Decide: Neighborhood Organizing in America. New York: Twayne Publishers.

Folsom, F. (1991). Impatient Armies of the Poor: The Story of Commonage Action of the Unemployed, 1808-1942. Niwot, CO: Academy Press of Colorado.

Fried, Eastward. (1997). Communism in America: A History in Documents. New York: Columbia University Printing.

Goldberg, G. (2015, Jan or February). Where Are Today's Mass Movements? : What can we larn from the millions who demonstrated for jobs, authorities relief, and commonage bargaining rights in the 1930s. Dollars and Sense.

Grossman, R. (2011, Oct 30). Today's economic protests echo anger of the Great Depression. The Chicago Tribune.

Hallgren, Yard. (1932, May 11). Help Wanted-for Chicago. The Nation.

Hallgren, Thousand. (1933). Seeds of Revolt: A Written report of American Life and the Atmosphere of the American People During the Depression. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Lasswell, H. and Blumenstock, D. (1939). Globe Revolutionary Propaganda: A Chicago Study. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Lorence, J. (1996). Organizing the Unemployed: Customs and Union Activists in the Industrial Heartland. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Lucia, D. (2010, May). The unemployed movements of the 1930s: Bringing misery out of hiding. International Socialist Review, 71.

Morrow, F. (1932, February 24). The Workers Demand. The Nation, 134, 222-224.

Piven, F. and Cloward, R. (1979). Poor People's Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail. New York: Vintage Books.

Ross, M. (1933, March i). The Spread of Barter. The Nation.

Storch, R. (2009). Red Chicago: American Communism at its Grassroots, 1928-35. Urbana and Chicago: Academy of Illinois Press.

Valocchi, South. (1990). The Unemployed Workers Movement of the 1930s: A Reexamination of the Piven and Cloward Thesis. Social Problems, 37(2), 191-205.

Valocchi, S. (1993). External Resources and the Unemployed Councils of the 1930s: Evaluating Vi Propositions from Social Motion Theory. Sociological Forum, 8(iii), 451-470.

Weyl, N. (1932, December 14). Organizing Hunger. The New Republic, 117-120.

williamsthoutencers80.blogspot.com

Source: https://sites.evergreen.edu/ccc/foodhousing/the-chicago-unemployed-movements-protests-for-food-and-housing/

Post a Comment for "Protest Form Agains Unemployment Benefits Illinois"